Hallucinations Are a Feature, Not a Bug

One thing that becomes hard to ignore with generative AI once you get past the initial wave of amazement is their tendency to hallucinate. Inaccuracies in answers and artifacts in images reveal the AI’s true lack of understanding. Remember how much trouble they had generating hands early last year? Money and engineering effort are pouring into the space to address this issue so that these tools can be used for more critical applications, with code generation being a major focus area.

But, striving to eliminate hallucinations from LLMs misses the point; these quirks are where the real transformative potential lies. To really take advantage of the potential productivity gains in software development, we need to be building our programs so that whatever code the LLM produces is working code, rather than tirelessly tweaking the LLM to output exactly what we have in mind. In entertainment, a 99% perfect image or video is fine; any imperfections add character if they’re noticed at all. Yet, in programming, while the program needs to accomplish a goal, embracing the unpredictable output of LLMs can lead to new innovative solutions at orders of magnitude higher productivity than traditional approaches.

A Bit of Programming History

One way we can look back at the history of software development is as a pendulum swinging back and forth between a precise, scientific, formal approach and a more informal, interpretationist, hermeneutic approach. Each approach has its strengths and weaknesses, and for exactly this reason the dominant approach in the industry changes back and forth as new capabilities are discovered and the strengths of one side are favored over the other.

If you’d like to go further into these two schools of thought, Avdi Grimm has a wonderful talk called The Soul of Software where he does a great job of introducing the concepts. To go even further, he references a book Object Thinking by David West that goes into a lot more detail.

If we start our brief history at structured programming in the 70s we start more on the formal side of the spectrum. We can then look at the rise of the “fuzzy intuition” approach of Object Oriented programming and Smalltalk as the pendulum swinging the other direction. This enabled the industry to really explore the capabilities of the increased performance of our computers, thanks in part to Moore’s Law, and the invention of the GUI for consumer and business applications.

Over time as useful techniques and patterns were discovered, the pendulum swung back to the formal side and we saw C++ and Java take center stage for a while. These languages and their frameworks systematized the looser approaches of their predecessors, reducing the variation in implementation and enabling teams to grow larger and move quicker for a while.

Then right around the mid-2000’s we had another swing back to the informal. This swing coincided with the rise of Web 2.0 – Ruby and Javascript were the big drivers here. Smaller teams were able to do more more quickly, and we saw an explosion of ideas and experimentation on how best to interact with this new paradigm of fast internet, cheap storage, and interactive web apps. It took roughly until the mid-late 2010s for things to stabilize again, it is no coincidence that Typescript, Rust, and Go really rose in popularity when they did.

So here we are again in early 2024 with the industry over on the formal side, while at the same time LLMs and generative AI provide a brand new territory to explore.

Horseshoes and Hand Grenades, or “Close Enough”

So, how exactly do we embrace the hallucinations of generative AI in software in an informalist way while still building working software? There are two main principles we’ve found so far to operate this way that we’ll be digging into in this post.

First, from a UX perspective – you need to design things in a way where you have to expect things to be at least a little wrong. This means presenting approvals to users and giving them the ability to easily edit and correct anything that comes back.

One great example of this is the Meals.chat Telegram bot by James Potter. This chatbot lets you send it a photo of what you’re eating and it estimates the calories, macros, and most likely ingredients. Built into the experience of it is a prompt from the bot that asks whether anything looks wrong, and if it does, allowing the user to reply with any changes to be made.

For dealing with hallucinations from a code perspective, we can take cues from Postel’s Law: “be conservative in what you do, be liberal in what you accept from others”. More dynamic languages like Ruby make following this principle a lot easier.

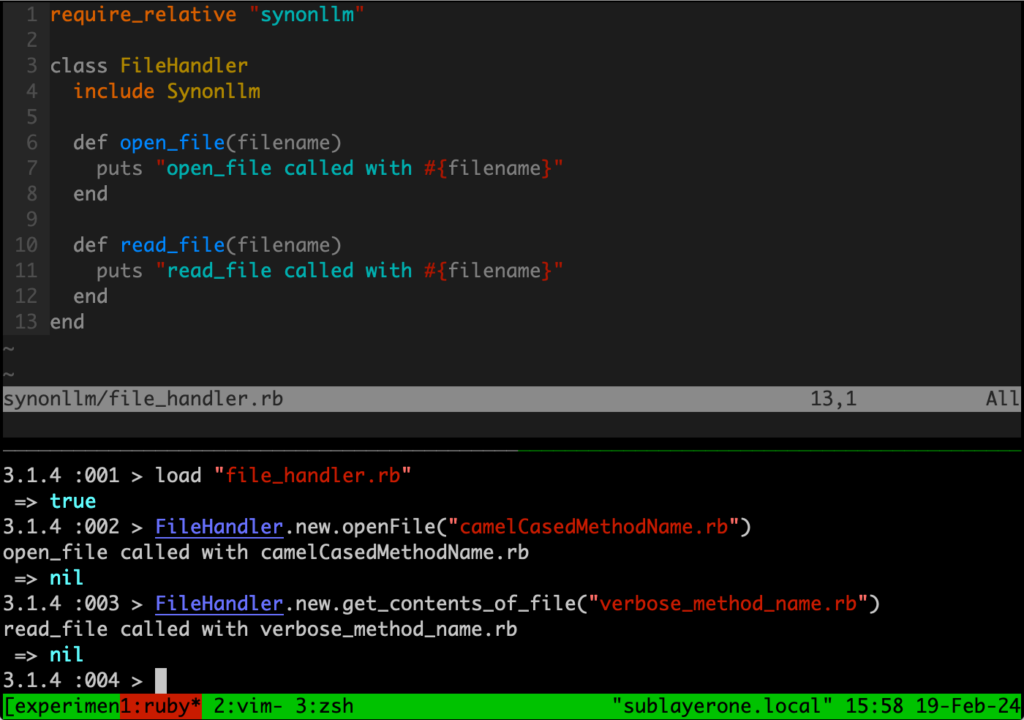

One example of this in action is this Ruby module named synonllm. When working with code from an LLM, you can generally be pretty confident in it intending to do what you asked it to do, but the trouble starts when you get into the fine details. Sometimes it doesn’t get method names right, like giving you something camelCased instead of snake_cased or just using the wrong method name completely.

Ruby gives us easy to use hooks to allow us to be liberal in what we accept from the LLM. We’re able to introspect on the action we’re trying to perform and figure out if there’s some way for us to accomplish the task the LLM wants to accomplish even if it isn’t exactly right.

For the programmers in the audience, you can see it in action below (Github Gist):

This post is already getting pretty long, but I have plenty more examples of how we’re doing this in code, this is just the tip of the iceberg. Think of how much more fun we can have with method_missing, or maybe with monkey patching.

Changing Perceptions and the Path Forward

In “Programming Extremism”, Michael McCormick calls the formal versus informal split I mentioned above “an ancient, sociological San Andreas Fault that runs under the software community”. I see it as an important tension and valuable back and forth depending on what is needed at the moment. And in the moment we’re in right now, I see a lot of opportunity in taking a more informal approach when building software with LLMs. Opportunity in making applications simpler to implement, easier to modify, and inventing new types of applications we haven’t been able to imagine before.

For those of you who are drawn to this approach, we’re building a place for you to share, experiment, and grow. Join our community of like-minded programmers who are exploring the untapped potential of generative AI. Whether you’re just starting out or have been a programmer through some of the pendulum swings I mentioned, we’d love to have you join us and share your insights and experiences. Come join our Promptable Architecture Discord and keep the conversation going!